“You’re given the form, but you have to write the sonnet yourself.”

–Madeleine L’Engle, A Wrinkle in Time

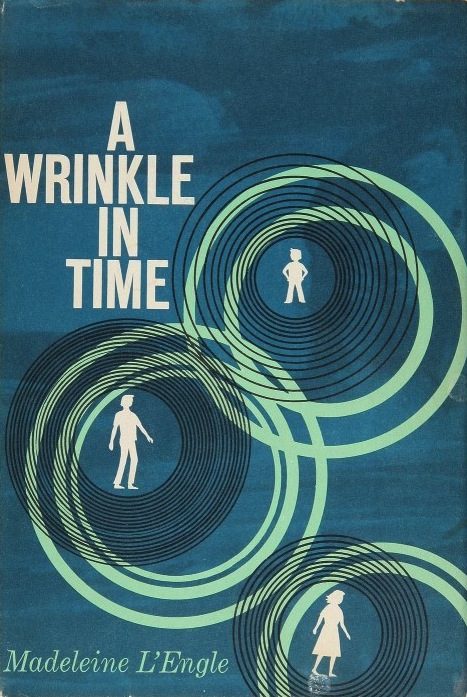

I remember as a young kid being intrigued by the dust cover to my older sister’s first edition copy of A Wrinkle in Time. The dark, storm blue background with a series of concentric circles surrounding three silhouetted figures may have been simple, but it set up a beguiling whirl of mystery.

Where were they and what was going on? And the equally enticing title… what could A Wrinkle in Time epitomize except adventure? Adding to the allure was the author’s name, Madeleine L’Engle, which to my seven-year-old ears sounded somewhat exotic. All these components added up to a promising read, though—until now—I never got any farther than the well-worn and off-putting opening throwback line, “It was a dark and stormy night…”

Wrinkle (first published in 1962) centers on Meg Murry, an awkward girl with glasses for nearsightedness and braces on her teeth. She considers herself an overall “biological mistake,” but in many ways, she’s a typical teenager in her myopic self-evaluation. That being said, her family life is a tad unconventional. At the start of Wrinkle, Meg’s brilliant physicist father, who’d been working for the government “on a secret and dangerous mission,” is missing and no one is talking about it. Meg’s mother is as beautiful as Meg is awkward, and she is every bit Mr. Murry’s equal. But instead of going on the journey to find him, Mrs. Murry stays behind to watch the ten-year-old twin boys, Sandy and Dennys (they don’t have much of a role in this initial exploit but a future volume is dedicated to them).

Instead, Meg’s youngest brother, Charles Wallace—believed by many to be a simple child but in fact a five-year-old genius who speaks in sophisticated sentences, having skipped the “baby preliminaries” altogether—is going with Meg to find their father. A neighbor named Calvin who has minor psychic abilities also tags along. And it goes without saying that Meg has a bit of a crush on the handsome Calvin.

Three celestial beings, cleverly named Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which, descend from the heavens, two appearing in the shape of witches while the third is in the moment of materializing but never quite does. The Three W’s have come to whisk the children away (which kinda happens fast without a lot of explanation, but I bought into it) and help in the search for Mr. Murry. The W’s can take other forms, including a massive, winged centaur-type creature big enough for the children to ride as they travel through several worlds, with The W’s guiding the children with wisdom and gentle prodding. Still, the children must make the jump through time and space alone and that takes some getting used to since it’s a jarring, dizzying experience referred to as “tessering” (a play on tesseract, which was advanced tech lingo for a young adult novel of the early 1960s and an example of how Wrinkle challenged narrow-minded expectations of the genre).

Early in the book, a villain referred to as The Man with Red Eyes has Charles Wallace under hypnotic control. Meg’s brother drones, “Meg, you’ve got to stop fighting and relax. Relax and be happy.” Of course, she continues to fight the battle of the mind to free both herself and Charles Wallace. This theme of fighting conformity seems at odds the familiar image of ‘The Innocent 1950s’ when the book was written… think Leave It to Beaver on the surface, but underneath is Eisenhower’s cautioned military-industrial complex working like a smooth, greased machine. Case in point: On the planet Camazotz, our young interstellars come face to face with a disembodied brain called IT after finding the being housed in the CENTRAL Central Intelligence Department. From IT, they confirm their suspicions that all citizens on Camazotz do exactly the same thing over and over as not to disrupt the general flow. Here the planet is ‘perfect’ in appearance but has deep-rooted dysfunction because there is no originality.

“As the skipping rope hit the pavement, so did the ball. As the rope curved over the head of the jumping child, the child with the ball caught the ball. Down came the ropes. Down came the balls. Over and over again. Up. Down. All in rhythm. All identical. Like the houses. Like the paths. Like the flowers.”

One mother is alarmed because her little youngster is bouncing the ball to his own inner drummer and—egads!—accidentally drops it. Another child, a paperboy, is unhinged by our travelers’ routine questions and pedals away in fright. So what’s the solution to fighting Red Eyes, IT, and The Black Thing that they both work for and represents evil itself? Simple. People united and working together can make a difference, but only if the individual characteristics that make up their identities shine through to enhance the whole. Conceal your gifts and run the threat of being a zombie.

Wrinkle’s enduring popularity derives chiefly from Meg Murry, a teenager hitting that in-flux age when we crave acceptance, and to be liked for our own judgments. It is also the age when we come to realize our parents are fallible. When Meg finally locates and frees her imprisoned father, she had hoped he would take her away and all would be aligned once again. Instead things get worse, and it’s up to her to solve their predicament by reaching deep inside herself for the answers.

Of course, this book can’t be mentioned without referencing the strong religious overtones that thread through the tale. I read the book before looking over any opinions past or present, and afterward, I discovered via The New Yorker that concern over Charles Wallace being viewed as a Christ-like figure may have been a hard sell. But I didn’t get that vibe… more like he was an incredible prodigy, the likes of which has not yet been encountered (that’s not too much of a stretch for a science fiction/fantasy book, right?). Nonetheless, the main contention for some religious groups is when Charles Wallace is excited to learn famous figures in history have been battling evil for centuries. Mrs. Whatsit says, “Go on, Charles, love. There were others. All your great artists. They’ve been lights for us to see by.” Then the wunderkind groups Jesus in with other historical figures like da Vinci, Shakespeare, Bach, Pasteur, Madame Curie, Einstein, etc. But if this throws your planet off its axis, then tessering away may be a good plan for you.

On the other end of the spectrum, A Wrinkle in Time is not going to satisfy demanding sci-fi fans with its lack of hard science and using faith to solve problems (just take a look at that last sentence of last paragraph). But for younger readers and those who enjoy classics, Wrinkle is still a great read. Much has been made of the book’s inspirational power for young children, and I have a first generation testament to that. It was my sister’s favorite book growing up and she could have stood in for Meg: gawky, quiet, and removed, she found comfort in Meg’s first adventure—of not only searching for her father, but in self-discovery of her individual strength. When I told her I would be offering my take on her favorite book she, now at 55, reminded me to be “open minded” since I was reading it an age well past its intended target audience.

And I was, big sister. With some reservations. Wrinkle was the first children’s book published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. It became a cultural bestseller, changing the way readers looked at children’s fiction, and is still available in hardcover fifty-three years later. A Wrinkle in Time, though a bit dated in places, holds up well.

David Cranmer is the editor/publisher of the BEAT to a PULP webzine and the recent anthology collection, The Lizard’s Ardent Uniform and Other Stories.